Literacy is a Social Justice Issue!

About the Episode:

Jeannette Roberes is an author who has worked as a speech pathologist, software engineer and educator. She has spoken in over 40 countries and has earned recognition in The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, among other professional acknowledgements. Jeannette’s commitment to life-long learning is noted through her LETRS® early childhood facilitator certification, Fast ForWord® and PROJECT READ® curriculum certifications. Her debut book, Technical Difficulties: Why Dyslexic Narratives Matter in Tech, has received 5 star reviews across Goodreads and Amazon. Jeannette is the chief academic officer of Bearly Articulating.

In this episode we chat about:

What do we mean when we say "literacy is a social justice issue"?

What are some of the contributing factors?

How does this impact learning?

Why do we need to pay more attention?

Episode Transcript

Hanna:

Welcome back to another episode of the My Literacy Space Podcast, today I'm talking with Jeannette from Bearly Articulating. Welcome Jeannette.

Jeannette:

Thank you very much, Hanna, I feel very welcome in your space today.

Hanna:

I'm really excited to talk today about a really passion area for me, and this is something that I think we are really starting to put some of the pieces more together about how much literacy is a social justice issue, and I want to talk about why are we saying that phrase? What does that phrase mean? And expand a little bit on thoughts about that.

Hanna:

So I wanted to start, first of all, with just a general definition of social justice, because this gets a lot of pushback, or maybe we're not understanding clearly exactly what social justice means, and so I'm taking the dictionary that's created for, The Young Activist's Dictionary of Social Justice, this is a book that I've been sharing, it's a picture book, but a dictionary picture book. And it has really fantastic social justice terms, and then it also includes fantastic stories about young activists, and the author says, "The idea that all human beings deserve equal respects, right and freedoms."

Hanna:

So we're starting from the biggest definition, but I want you, first of all, to introduce yourself, and then we're going to jump into that being the base for today, what we're going to be talking about. So tell us a little bit about yourself, and then give your definition of what it means to say literacy is a social justice issue.

Jeannette:

All right, thank you for opening the floor for me first and foremost I love the picture book as a mean of helping to bring awareness to definitions that are all over the place, everybody has an idea of what they think it is, but using those pictures, potentially gestures, is so essential to our students with the greatest need.

Jeannette:

So I am Jeannette Roberes, formerly Jeannette Washington, I am the Chief Academic Officer of Bearly Articulating. I've worked as a speech language pathologist, a software engineer, a librarian, a substitute teacher, I've done a little bit of everything. My favorite role is as mother and also as a dyslexia advocate. Those two things are my absolute fave. So when we are talking about literacy we often hear that it's the fundamental human right, and that it's the foundation of lifelong learning. It's fully essential to social and human development because it reduces human poverty overall.

Jeannette:

Human poverty is certainly something that we're seeing a lot of as inflation increases all over the world, so just not in the US, or not in Canada, but we're really seeing a whole lot of it, we know that literacy helps individuals make informed decisions, and it helps them participate fully in the development of their societies. So when we're talking about social justice, we know that it's all about providing equal economic, political, and social rights, particularly to those with the greatest need. So I hope that answers your question and summed up a little bit, added a little flare there.

Hanna:

Yeah, I love that, because I think that sometimes we think maybe a little bit too linear, or we think in a box, and we have to really start unpacking exactly what this mean and the way that it's impacting, as you said, the most vulnerable people on the planet, and as well as really making sure that we are going to start doing our best at addressing those issues.

Hanna:

I recently read a book by Kimberly Parker called Literacy Is Liberation, and in the very beginning she talks about the anti-racist literacy expert Tricia Ebarvia, I think her name is, and I've not never heard of her so I'm going to do it deep dive into Tricia as well. But she was talking about in the beginning that, she says this, "The internal work matters a lot. You cannot disrupt if you don't understand how systems of oppression work, you cannot understand how systems of oppression work until you come to terms with how they have worked on you." That was a very impactful statement to me as a white human being because I have a place of privilege where I don't always stop to think about how have those systems of oppression favored me and put other people at great risk.

Hanna:

And so I think when I think of literacy as a social justice issue, for me in my work of tutoring and thinking of kids that have dyslexia, have reading disabilities, have other pieces that also impact their access to that information, whether it's educators are not educated correctly in the science of reading and structured literacy and what that looks like, it might be access to content, access to resources, accessibility is also a huge obstacle right now. I loved when... First of all I wanted to just shout you out because your graphic images speak to me, because I love seeing those pieces visually and seeing where you've unpacked a few things. And so one of the ones that you had done a while ago was you were talking about how does privilege impact dyslexia identification, it was one of the graphic images on your Instagram feed, and I wanted to talk about what are some of those contributing factors that impact literacy, and maybe specifically you can speak about dyslexia.

Jeannette:

Absolutely. So literacy strengthens the capabilities of individuals to access healthcare, political opportunities, and so much more, though when we're talking about dyslexia, and we're looking at the cost of assessments, we're looking at the organization that provide wraparounds to students who are falling between the cracks. We look at how the Black families can oftentimes stigmatize individuals who are not necessarily reading or writing at the pace of their counterparts.

Jeannette:

There's so many different layers to that that we can unpack, but I will say, from what I've seen personally, just having access to those private assessors, because a lot of times if you are in a public school setting the teacher and the health or the allied resources at your school may not have the bandwidth to assess the students, so having access to those outside individuals who can come in and provide an assessment and label what it is that is ailing you, or that you feel has been a challenge for you as you are learning to read.

Jeannette:

So those are probably two or three of the things that I would say are the barriers, because I even think of the wheel of oppression, and I look at the fact that though we are all different, all of us have privileges, maybe the privilege is that you live in a first world country. Maybe the privilege is that you have access to great healthcare because it's through your spouse. Maybe the privilege is your religion, and the fact that the majority of your community practices that religion so you don't feel alienated. Maybe it is your gender.

Jeannette:

There are so many different privileges that we are bringing to the table as we're identifying ourselves, and it's just important to acknowledge that, we're doing work, we're doing the work. And as you said, you're a white human being, I read something recently about when we are advocating and we're using our spaces, our platforms, to really make or draw awareness towards different causes, however we're not educated properly on those particular causes, it may do more harm than good, if that makes sense.

Hanna:

Totally, yeah.

Jeannette:

And I don't know if I've ever thought about it until I read it, and I took some time to really process that, and it was like, wow. It's one thing to be shouting out at the rooftop about this particular cause, but am I drawing more attention to myself, or am I really advocating for this particular issue?

Hanna:

Yep. Okay, so that went right into, Kimberly Parker in her book, Literacy is Liberation, also says, if you want to be an educator who is grounded in culturally relevant instruction, and who considers themselves to be a culturally relevant educator, you have to be willing to mess up, and then continually strive to then do better. So if we're supposed to be, if our call is, and we really want to be those people who make a difference, we're really becoming a co-conspirator of truth and justice. But it starts with us as the individual, before we're shouting it, like you said, to the masses, right?

Hanna:

So it's really doing that internal work, and I love that in her book, because we can't do that external work and understand those systems of oppression, and we can't understand what impact different pieces are having on our students without really looking at those bigger pictures, so I think that I love what you just said there. So let's talk about then why do we need to pay more attention to those barriers, to the obstacles, to educating ourselves, why is that really key maybe right in this moment right now?

Jeannette:

What I would say is as we are doing that work, so to speak, we need to ask ourselves questions, and this is based on our original conversation around dyslexia. So we need to start asking ourselves, what does dyslexia mean to us? What does a dyslexic person look like? When you think of dyslexia, what comes to mind? Those type of frame of references are really going to anchor us in how we move forward. When you think about dyslexia, or when it comes to your mind, are you seeing a white little [inaudible 00:11:14] is this something that you stereotypically see and you don't acknowledge that dyslexia affects little girls, maybe Black little girls and Indian little girls, and all of the little boys and girls, and those who identify as non-binary as well. What are you really seeing and thinking about on that level?

Jeannette:

So I think it's important that we start asking ourselves those probing questions, and then we also look at those common myths that exist, reading and writing letters backwards, or dyslexia is only seen after second or third grade, or that it's a medical diagnosis. Some of those things need to be addressed right after we are looking inward and identifying some of the biases that we possessed. There was a quote by Resha Conroy that really stuck with me, it says, "For Black students with dyslexia, their difficulty acquiring reading raises no alarms due to their low expectations, and therefore excludes them from a dyslexia diagnosis." So I often think about that, and you mentioned something earlier about teachers not being quite prepared, that's another part of the bigger scheme of things as well.

Hanna:

Yeah, exactly. In Kimberly's book as well, Literacy is Liberation, she talks about five key points that are your takeaways from the book that she really wants to help people understand, and one of them is, what really hit me the hardest too was incorporating specific high leverage literacy practices that normalize the high achievement of all students, especially BIPOC students.

Hanna:

You were saying that a couple minutes ago, we have prejudice in when we look at that student, or this student, or that student over there, and even when we are thinking about services, bringing in services, we're checking constantly, we need to be checking our biases of who are we getting access for, and like you said, those barriers of assessment and access to healthcare, and pieces where it's a bigger picture in so many ways, And I think that's what I want to keep drawing attention to for people to keep understanding and digging in to self reflect on our past practices, our current practices, and where do we want to be in the next month? Yes, we want to have access for everybody, and what does that look like? What kind of systems are we going to have to work through and support our kids to be able to access that?

Hanna:

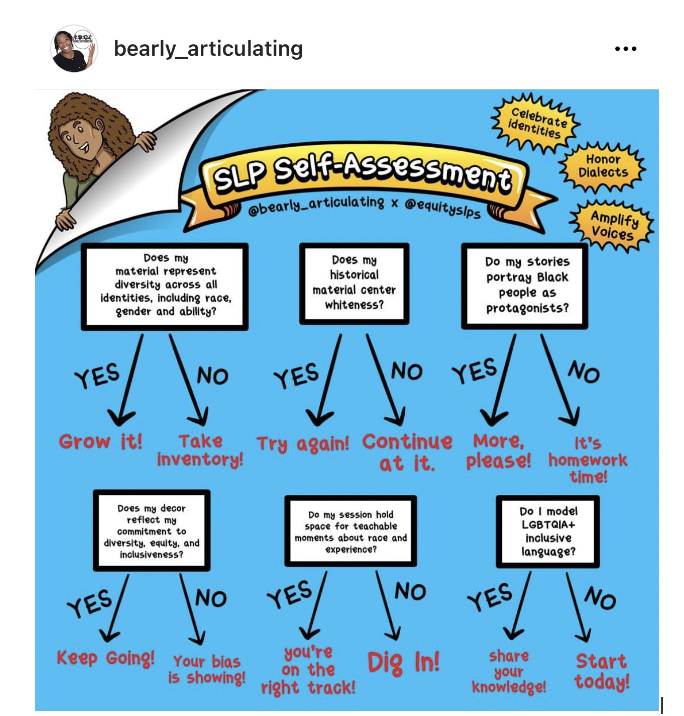

One of the graphic images that I really loved, and I can't remember when it was, but I put in my notes here because I thought it was so good that you had created with equity SLPs as well, and it was like an SLP self-assessment, and I loved it because I thought we could do, this educator self-assessment could be the same thing. So you were talking about, it has this great graphic of the yes, no, a flow chart. So does my material that I'm using represent diversity across all identities, race, gender ability, if yes, grow it, and then if no, take inventory, so that you had all these really fantastic ways that we can tangibly start to think about the obstacles we are putting in the path of our students. Tell me more about that graphic, because I loved, I just loved your thought process behind thinking about that.

Jeannette:

So for an SLP and an educator to suspect dyslexia, or any other language based learning disorder, that professional must first expect that child can be taught to read ,or be taught to speak. So given the research on implicit bias and those lower teacher expectations, the reliant on unexpected difficulties negatively affects Black children, especially those who are on that dyslexic continuum. So when I created that with one of my colleagues, we were really looking at ways, and this was right around the time where we saw a lot of injustices happening in the US, and it was at a precipice, we were all fed up, everybody was fed up.

Jeannette:

And so we were looking inward, and then from our inventory that we took within ourselves, we decided to start looking at the communities and the schools that we serve. And we wanted to really look at how we can create opportunities to really showcase and highlight students who are not getting all of the attention, who are not getting all of the representation.So we just sat down and did a brainstorming session, and we didn't want it to be in a sense where we were making educators, SLPs, and related service providers, we didn't want them to feel ashamed about what they didn't know. We didn't use any phrases where we said, go back to the drawing board because you're doing it wrong, it was more grow it, take inventory, look within.

Jeannette:

So we felt that would be a way to passively provide some encouragement for those who were possibly doing the work, or considering doing the work. And it was a great brainstorm session, and it's funny you said that, the colleagues name is Erica, and Erica and I need to get together and work on something like that again, because I think it was such a fundamental collaboration with we are coming from two different districts, we had two different experiences, who separate identities, and we were really bringing forth some information from what we saw in the field.

Hanna:

Yep, I just love that one because it was a really great way to start that beginning thinking of checking your biases, checking your understanding, and I love that you said not from that shame-based perspective, but this, okay, I'm going to dig in. Is my bias showing? Oops, I'm going to fix that and I'm going to move forward.

Jeannette:

Because what we saw is when people are unaware of their biases, there is no internal check to [inaudible 00:18:11] and that increases the likelihood of perpetuating biases. We definitely wanted to tap in from every angle with that.

Hanna:

I love that. So what would be some resources that you would, if there's picture books or podcasts or other articles, we're going to link everything in the show notes, but some resources for educators, SLPs, even families, when we know now that we need to pay more attention to this important topic of literacy being a social justice issue, what kind of resources can we start to read, listen to, pay attention to?

Jeannette:

Okay, so we've talked about some of the barriers, so I would say on the breakthrough end we need to continue to highlight those who don't necessarily look like us and bringing their voices to life so that we can all see the intersection between our lives, our identities, even as we talk about dyslexia. And we have so much to understand, and so much work to do to become better advocates. We can collaborate with one another, like you and I are doing today, and that allied support staff, and we want to also bring parents in as active participants as we're setting learning goals, and we're looking at the bigger picture when it comes to making decisions that affect our learners. We want to seek training, support, flexibility, and resources as we will dive into a bit, that nurture, encourage, and responds to the needs of all learners.

Jeannette:

But when it comes to resources I would say some that I found very helpful are from JRCSLP, and that is her Instagram handle. I have products that I produce through Teachers Pay Teachers, you just simply need to search Bearly Articulating, and I like to bring a lot of information for those who look like me, and don't necessarily look like me, who have experiences like me, and don't necessarily have experiences like mine, Think Dyslexia, who has been on your podcast before, I would say that that is certainly a person you want to tap into. What we are talking about testing and assessment-wise, I think it's important that you are using materials that do not use language that is abstract to individuals who are using a very particular dialect. Think like this.

Jeannette:

There's so many ways I can go with this, I'm just thinking top of the mind, resources for myself, JRCSLP, Think Dyslexia, is there anybody else? I work with a nonprofit called Smiles for Speech and I absolutely adore the work that Smiles for Speech does because they seek to collaborate, not to try to fix. And I think that's important as we're going in on a professional level, that we're not trying to fix any problems, but we're trying to collaborate with those individuals who are already there, getting some understanding about the situation and what needs to happen on a collective conscious front.

Jeannette:

So I hope that provides you all with a little bit more context. I will think of more resources, you can also DM me personally and say, hey, I'm looking for X, Y, and Z, and I may be able to provide you with more depth, but right now I'm just thinking of so many different things in real life.

Hanna:

I know, and you're right, there's so many different ways because we really want to make sure that we're thinking about all of those barriers, and then, okay, what did you call it? You said the barriers and then the breakthroughs, is that what you called it?

Jeannette:

Yes.

Hanna:

I love that. And that gives us that hope of what do we need to do to address these? We have to be aware of them, and then like the biases, the barriers, and then the breakthrough. Hey, we've got a triple B there, that's awesome. So I think that's a really great, and you're right, Think Dyslexia is @theDrLauren on Instagram, and she was on my podcast talking about dyslexia, and she also did a really great summit presentation for my Science of Reading Summer Summit that I had done in the summer, and she was talking about things of even how the disproportionate access for BIPOC children with dyslexia and their access to the information, but the assessments, and things like that. So she has a great podcast that is brand new as well, so definitely check out @theDrLauren.

Hanna:

So thank you very much, Jeannette, for your time. Any last leaving thoughts that you want to just really help us understand the importance of doing the work and continuing the work once we've dabbled our toes in it?

Jeannette:

I would say to consider how the lesson, the activity, or the assessment will honor the identity of that suit. That is something that needs to be taken into account. I would also say that you should do some research on the pipeline to prison, and adult amplification bias, as well as culturally responsive resources and what that would look like for you in your therapy room, in your tutoring session, in your classroom. A couple questions to consider, who has the loudest and the lowest voice? Who am I representing, and who am I not even considering? And how are your identities, privileges, and position of power impacting how you are showing up every day and providing value to students?

Hanna:

Love that. So we will have a list of people to follow, resources to check out. I know that Literacy is Liberation was a really fantastic book that I read recently, and Kimberly N. Parker is just phenomenal, the work that she is doing is really wonderful. So thank you again so much for your time, I cannot wait to share this podcast with everyone. Thank you Jeannette.

Jeannette:

Thank you.

Resources mentioned in the episode:

The Young Activist’s Dictionary of Social Justice

Amazon Canada affiliate link:

Amazon US affiliate link:

Literacy is Liberation by Kimberly N. Parker

Amazon Canada affiliate link:

Amazon US affiliate link:

Think Dyslexia with Dr. Lauren

Website: https://www.thinkdyslexia.me/

Podcast: https://www.myliteracyspace.com/blog/how-to-supportyour-dyslexic-child

Connect with Jeannette

Instagram: @bearly_articulating